The Mysterious World War II Bunker Atop Oregon Coast's Tillamook Head

Published 04/29/2018 at 4:56 AM PDT

By Oregon Coast Beach Connection Staff

(Seaside, Oregon) – The grand, sweeping even looming landmark of Tillamook Head on the north Oregon coast is quite immersed in history. It goes back 15 million years when it was layers upon layers of lava. It saw its first visit of white Europeans in the form of Lewis and Clark, which gave the area its first rave tourist review. Tillamook Head also watched a major lighthouse come into existence then fade away, and it even saw a helicopter crash in the 1980s. (Photo of the bunker courtesy Tiffany Boothe, Seaside Aquarium).

One striking, awe-inspiring tidbit of its history is still a murky mystery, albeit one seen periodically by the few adventurous hikers that dare to trek over its six miles of rugged forest and jagged, plunging cliffs.

Includes exclusive listings; some specials in winter

In Cannon Beach:

Includes rentals not listed anywhere else

In Manzanita, Wheeler, Rockaway Beach:

Some specials for winter

In Pacific City, Oceanside:

Some specials for winter

In Lincoln City:

Some specials for winter

In Depoe Bay, Gleneden Beach:

Some specials for winter

In Newport:

Look for some specials

In Waldport

Some specials for winter

In Yachats, Florence

Some specials for winter

The old World War II bunker there, about 1.5 miles from the Cannon Beach end of the trailhead, is a weird and slightly spooky addition to the hike. Now, all you find are a few errant chunks of moss-laden concrete and metal, and that mysterious bunker that’s about the length of a school bus. Once upon a wartime, however, this spot buzzed with the secret activities and daily grind of military men set with the task of guarding these shores against a possible air invasion from Japan during World War II.

You’re looking at ruins and remnants these days, but you’ll see no plaques or educational signage. Even in this modern age of frenetic internet information overload, there’s absolutely nothing written about this ancient vestige from the early ‘40s. Nothing.

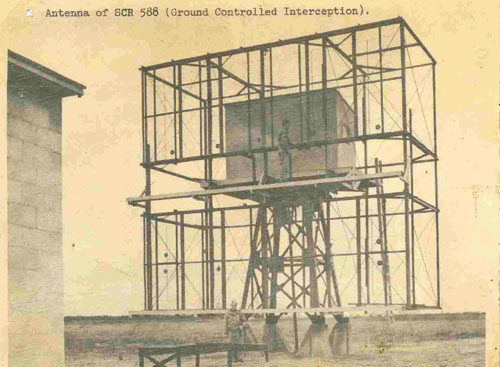

Photo OPRD: the type of antenna used by the SCR-588 radar system.

Except, it turns out, the military historians at Fort Stevens State Park – about 10 miles to the north – have some information. But not a lot. What they do have is a fascinating, if not bare bones, glimpse into wartime on the Oregon coast.

John Koch is a historian at Fort Stevens and a park ranger with the Oregon Department of Parks and Recreation (OPRD), which technically oversees this north Oregon coast headland. He’s not giving out much information – mostly because there isn’t much left. But OPRD is also concerned about people doing stupid stuff there, like trying to get in (you won’t like the bats, we’ve been warned). So he isn’t imparting everything.

“I can tell you that the site was utilized by the U.S. Army Air Corps for about one to one and a half years during WW II,” Koch said.

Exactly what years he either wouldn’t say or couldn’t. More mystery.

The bunker was part of a radar station that kept a lookout for enemy aircraft. In fact, this reinforced structure held up the gigantic antennae, which were about 30 feet tall, judging by the historical photograph provided by OPRD.

It was manned by a crew of eight men, who worked in shifts around the clock.

“Their job was to operate a large radar antennae with the intention of spotting any incoming Japanese aircraft,” Koch said. “There were several of these stations along the Oregon coastline with the Tillamook Head location being the largest. Each of these stations were connected to a network of communication centers that included air bases near Portland and Seattle. If an enemy squadron was detected word would be transmitted to these centers so that our defense systems could be initiated.”

That meant, according to Koch, that aircraft and ships could be dispatched to meet the enemy. Luckily, Oregon never experienced that full invasion. Although there was a run-in with a Japanese sub at Fort Stevens in 1942 and an incident with an explosive on the southern Oregon coast.

The radar station at the top of Tillamook Head had the call sign “Juliet-two, three,” or J-23.

Those serving there were a part of the 4th Air Force, Western Defense Command, Pacific Coastal Frontier. They included the AWS (Air Warning Service) observers and GCI (Ground Controller Interceptor) units, Koch said.

Even more amazing, the bunker and antenna were only one part of the whole operation. There was a full camp here once. It had a pump house and a barracks / house with a mess hall and store rooms. A total of 50 to 100 men worked and lived at J-23.

In fact, this whole camp was a set of temporary buildings known as a SCR-588 that were sort of mass-produced, a group of constructs that were almost a mobile unit. They were designed to be built up quickly and taken down quickly. One document provided by OPRD indicated: “Set is packaged for shipment in 55 units, weighing a total of 54,000 lbs. Largest unit measures 15.3' x 3.8' x 1.8'. Total shipping space is 3500 cu. ft.”

Another part of the military document indicates its mobility: “Buildings and tower can be built by Engineers in about 3 weeks. Radar can be installed by 5 men in 2 weeks.”

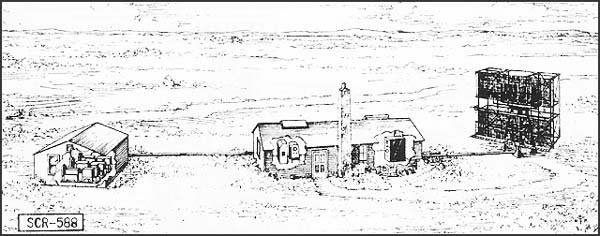

Courtesy OPRD: typical layout of an SCR-588 station in World War II, though not necessarily that of the J-23.

“The radar was so sensitive that all the nearby buildings had to be constructed of anything other than metal,” Koch said. “Even the barbed wire used to protect the perimeter of the camp had to be placed at a certain distance away. There was a reinforced concrete bunker that housed the apparatus and generators to run the massive radar antennae mounted just outside it. The cliff top location had a commanding view of the Pacific Ocean from hundreds of feet above the sea level, directly above the Tillamook Light House.”

Koch said a fairly large area in front of the bunker had to be cleared of trees. In fact the military document describes these requirements: “When operating as GCI, set must be sited so that a flat unobstructed surface extends at least 1/4th mile in the height-finding sector. Good GCI sites are extremely rare. For early warning, sets should be sited between 100 and 1,000 feet above an unobstructed surface.”

It’s interesting to note how many trees have grown back now. The area is under a dense canopy.

Koch described a bit of what went on there.

“The GCI unit consisted of 8-10 specialized crewmen made up of officers and enlisted men who worked in the bunker operating the equipment around the clock,” he said. “They directed friendly aircraft to the location of the enemy using their state-of-the-art electronic monitoring and computing devices. The radar allowed them to carry out this task day or night, in the fog or rain. It was capable of detecting an aircraft at a height of 5,500 ft. out to approximately 50 miles. By today’s standards this is not significant. But during WW II this was a game changer.”

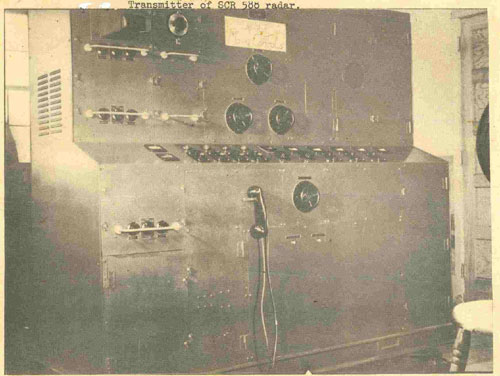

Courtesy OPRD: Inside the bunker during World War II.

The bunker housed generators to provide power, a restroom, several work rooms, the bulky contraptions used by the radar system, and a room with a heating system and air purification system – in case they were attacked with chemical weapons.

J-23 had a lot going on for a place that never had to send out a warning.

“Other personnel worked and lived in the facilities nearby, cooking food, fixing equipment, manning the phones, etc.,” Koch said. “If they needed medical attention, or to replace supplies, they traveled up Highway 101 to Fort Stevens.”

Changes are coming to the site, Koch said. It’s on a fast track to become a national historic site, which means some heavy fencing is coming to keep people away from it.

It’s also known as a hibernaculum – a nest for several species of bats, some of them endangered. Both situations may mean federal laws will become involved with those who damage it or try to break through the measures to keep people out of it. Oregon Coast Lodgings for this - Where to eat - Maps - Virtual Tours

Cannon Beach Lodging

Nehalem Bay Lodgings

Manzanita Hotels, Lodging

Three Capes Lodging

Pacific City Hotels, Lodging

Lincoln City Lodging

Depoe Bay Lodging

Newport Lodging

Waldport Lodging

Yachats Lodging

Oregon Coast Vacation Rentals

Oregon Coast Lodging Specials

More About Oregon Coast hotels, lodging.....

More About Oregon Coast Restaurants, Dining.....

LATEST Related Oregon Coast Articles

Producers of the Bay series on Wednesday, March 18, from 6:30 to 7:30 p.m. Oceanside events, Pacific City events, Lincoln City events, Garibaldi events, Tillamook events

A Staple for Oregon Coast Spring Break, Festival of Illusions Hits Lincoln Ci...

2026 Festival of Illusions, March 22-27. Pacific City events, Lincoln City events, Depoe Bay events, Newport events

Dusting of Snow for Much of NW Oregon Tonight a March Curiosity

Snow levels down to 500 ft tonight, with the Coast Range and Cascades seeing heavier impacts. Weather

Controversial Lodging Tax Passed by Oregon Lawmakers

While the measure helps wildlife and ranchers, it will increase hotel rates statewide. Hotel news, Astoria hotel news, Seaside hotel news, Cannon Beach hotel news, Manzanita hotel news, Rockaway Beach hotel news, Garibaldi hotel news, Pacific City hotel news, Lincoln City hotel news, Depoe Bay hotel news, Newport hotel news, Yachats hotel news, Bandon hotel news, Coos Bay hotel news, Brookings hotel news, Florence hotel news

Velella Velella Hit the Oregon Coast and Washington - But Something is Different

Many of the creatures are smaller than usual, indicating unusual conditions offshore. Marine sciences

Oregon State Police Fish and Wildlife Seek Help Finding Bull Elk Poachers

Cash awards are offered for information leading to arrests in this Prineville-area case. Sciences, eastern Oregon

Portland Event a Fundraiser to Bring Sea Otter Back to Oregon Coast

The Oregon Otter Beer Festival at OMSI takes place April 11 to support restoration efforts. Portland events, Pacific City events, Lincoln City events, Depoe Bay events, Newport events, Manzanita events, Cannon Beach events. marine sciences

Coast Guard Swimmer Dies After Week in ER: Washington and Oregon Coast Pay Tr...

Officials announced the death of Petty Officer 2nd Class Tyler Jaggers, prompting tributes across the region

Back to Oregon Coast

Contact Advertise on BeachConnection.net

All Content, unless otherwise attributed, copyright BeachConnection.net Unauthorized use or publication is not permitted