|

Oregon Coast Science Has Its Creepy, Gooey Side |

|---|

Covering 180 miles of Oregon coast travel: Astoria, Seaside, Cannon Beach, Manzanita, Nehalem, Wheeler, Rockaway, Garibaldi, Tillamook, Oceanside, Pacific City, Lincoln City, Depoe Bay, Newport, Waldport, Yachats & Florence.

01/15/08

Secrets of the Season |

Oregon Coast Science Has Its Creepy, Gooey Side

|

| The beach in front of the Tides by the Sea as it is today: lots of it didn't exist before the late eighties. |

(Oregon Coast) - Beyond the pretty sights and sites of the Oregon coastline, its lovely, calming ocean vibes and the memory-making moments that are created by a vacation here, there’s a layer of weird stuff. It’s one of those oddball secrets that sits below the surface of the usual tourism activities – quite literally below the surface. But if it’s something you’re aware of, it gives you whole new vistas to gawk at and enjoy while on these beaches.

In the worlds of weather, the ocean environment, the fauna and even the strange tales told by the rocks themselves in the geologic sciences, there’s more drama here than just the wave action.

New Chunks of Land in Seaside

The southern cove area of Seaside, with all its surfing glory and splashy waves, was not always what you see these days. There was until 20 years ago a lot less of it.

“A

huge landslide in 1987 added about 100 yards to the southern end of Seaside,

where the cove is now,” said Tom Horning, a coastal geology expert

living in Seaside.

“A

huge landslide in 1987 added about 100 yards to the southern end of Seaside,

where the cove is now,” said Tom Horning, a coastal geology expert

living in Seaside.

Weiss' Paradise Suites & Vacation Rentals - Seaside Unique Luxury Accommodations in Seaside. 1BR Suites,

1BR & 2BR Duplex Units and 3BR Houses, units for 2-8 people.

Rent entire property for 20-26. Close to beach, river and Broadway

St. |

Horning explains that Tillamook Head sometimes drops tons and tons of rocky material into the sea, which periodically changes the landscape. Back then, boulders and rocks from this particular landslide slowly filled in the cove area, extending one part out hundreds of feet. A new spit was formed by the rocks for a time, which locals used with glee to catch loads of fish. Fairly quickly, that space between the spit and the land filled in, creating an enormous dead tide pool for a few months. Eventually, sand and rocks filled all that in, as well as down the beach. The entire southern end of Seaside's beaches became wider after that.

Horning points to the building at the cove that is the beachfront section of The Tides by the Sea hotel. “Back when they first built this, the sea practically came right up to the building,” Horning said. “They had boulders and rip rap there to keep it away. After 1987, 100 yards of beach was created in front of that area.”

|

| Mole crab (photo Boothe) |

Freaky Mole Crabs

They show up in summer, usually late in the season, and do some kind of creepy things to the waves.

They are called mole crabs, but they don't pinch or bite. In fact, they have small feather-like appendages which they wave through the water to collect plankton. Instead of pinchers they have paddle-like legs which help them burrow quickly into the sand. Mole crabs swim and dig into the sand backwards - that way only their eyes are sticking out of the sand. You’ll see the waves appear to “bubble” as their vast numbers in the sands are tossed around by the tide and they struggle to burrow themselves into one spot.

You’ll notice these bug-like creatures washing over your feet in the late summer. You can feel the sensation of dozens of little something-or-rather’s zip across your feet.

|

| Photo by Boothe |

They dig themselves into the sand using a tail, which they utilize with a swirling motion, allowing them to change direction with whatever the tide is doing or wherever it’s taking them.

Instead of pinchers, mole crabs have adapted claws to help them dig in the sand. They also come with two sets of antennae: breathing tubes and feeding antennae.

They normally live on sandy beaches in the surf zone, usually buried in the sand with the breathing antennae sticking out. You’ll find them in the geographic range of Alaska to Chile, but only occasionally found north of Oregon. Northern populations are from larvae that ride the current up the coast.

|

| Colorful creatures can be especially vibrant in tide pools in Oregon (photo Tiffany Boothe, Seaside Aquarium) |

A1 Beach Rentals, Lincoln City. Perfect for large family vacations all the way down to a getaway lodging for two - with over 25 vacation rental homes to choose from. A breathtaking collection of craftsman or traditional beachfront homes, or oceanview houses – from one to seven bedrooms. In various areas of Lincoln City and overlooking the beach, with some in Depoe Bay. All kinds of amenities are available, like hot tubs, decks, BBQ, rock fireplaces, beamed ceilings and more. Some are new, some are historic charmers. Lincoln City, Oregon. 1-(503)-232-5984. www.a1beachrentals.com. |

Colorful Creatures from Inner or Outer Space?

“When you go out to a tide pool, are you seeing all there is,” asked Seaside Aquarium’s Tiffany Boothe. “Do you know what it is you're looking at? Can you determine whether or not what you're looking is an animal or a plant?”

Boothe said there is quite a bit people are probably overlooking on their often cursory glances or looks into the little colonies of life left by low tides. One of these is the wild and wonderfully colorful sea slugs – or nudibranchs (pronounced with a “k” sound at the end, not a ch sound). They come in such diverse shapes, patterns and colors it is impossible to see all the configurations.

|

| Flabellina triophi is one of the wild creatures you may find in a coastal tide pool (photo Boothe) |

Some 3,000 different species inhabit the world’s oceans and tide pools, ranging in length from 1/8 inch to 12 inches. They look like creatures from space, or the product of that esoteric mixture of art and computer algorythms called the Mandelbrot set (where computers take a fractal exercise and generate elaborate, colorful designs that are infinitely intricate).

All photos here taken by Boothe on different expeditions to coastal tide pools.

“Nudibranchs are marine snails, relatives of limpets and abalone,” Boothe said. “Through evolution they have lost their shell. In fact, the name nudibranch means ‘naked gills,’ referring to the fact that their gills are on the outside of the body. While most lack shells some species have a reduced or internal shell.”

Boothe said they come in all shapes, sizes, and colors.

Some nudibranchs are able to blend in with their environment by means

of cryptic coloration, while others brightly advertise their presence

to everyone.

200 different species call the Pacific Northwest home, making quite the

color splash in those tide pools you’re peeking into on the Oregon

coast. Click

here for a complete list of places to find tide pools on the Oregon coast.

|

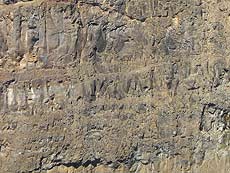

| Layers of lava flows are visible in the massive cliffs of Cape Meares, just north of Oceanside and west of Tillamook |

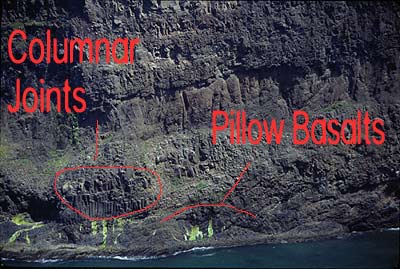

Spooky Geology in the Rocks of Cape Meares

Gazing at the massive cliff walls and their ragged features from the various viewpoints along Cape Meares is, understandably, one of the big pastimes at this amazing spot on the north Oregon coast. But if you know how to read it, a wild saga emerges. They are, in many ways, a slice of the Earth’s crust in this area, cut down the middle so we can – quite literally – see the layers.

Horning is a renowned geologist on the subject of anything coastal, with Seaside's Gateway To Discovery. He’s spent considerable time staring at the myriad of layers embedded in the rocks here, frozen in time from the Miocene period. He says these layers represent eons of massive lava flows that have piled on each other over millions of years, coming here from hundreds of miles away.

Cape

Meares is like a cutaway of the Earth, with layers of lava flows visible

in the rocks, covered by sandstone that was once an ocean bed

Cape

Meares is like a cutaway of the Earth, with layers of lava flows visible

in the rocks, covered by sandstone that was once an ocean bed

He says it all begins with a fiery situation over 15 million years ago, when a giant hole in the Earth’s crust spewed so much lava it scarred and seared its way across what was then Idaho and Eastern Oregon, until it reached the sea (which was several miles inland, perhaps as much as 75 miles east).

This is the same hole that now fuels the action at Yellowstone National Park. Continental drift pushed that weakness in the crust eastward over time, and it now lies there.

|

Tradewinds Motel, Rockaway Beach. All rooms are immaculate and have TV’s, VCR’s and in-room phones w/ data ports. Oceanfronts have queen bed, a double hide-a-bed, kitchen, cozy firelog fireplace and private deck. Both types sleep up to four people. Others are appointed for a two-person romantic getaway, yet still perfect for those on a budget. Elaborate oceanfront Jacuzzi suite has two bedrooms, kitchen, double hide-a-bed, fireplace and private deck, sleeping as many as six. For family reunions or large gatherings such as weddings, some rooms can connect to create two-room and three-room suites. Some rooms pet friendly. 523 N. Pacific St., Rockaway Beach. (503) 355-2112 - 1-800-824-0938. www.tradewinds-motel.com |

Essentially, these massive flows came again and again, separated by hundreds, thousands maybe even millions of years. No one is really certain how long between each eruption. The lava flows literally filled up the space in a prehistoric valley, locking its shape in time with the sturdy basalt rock that happens after lava cools. Eventually, that valley eroded away, leaving only the rock.

If

you look closely at the cliffs, you can see the layers piled up on top

of each other. Some layers appear as pillow basalt, which is formed when

the lava hits water and cools very fast, forming bubble-like structures

that aren’t as jagged as the regular layers.

If

you look closely at the cliffs, you can see the layers piled up on top

of each other. Some layers appear as pillow basalt, which is formed when

the lava hits water and cools very fast, forming bubble-like structures

that aren’t as jagged as the regular layers.

When the others layers simply cooled in the air, it sometimes created strange shapes, which can also be seen at the bottom of the cliffs: little bundles of what look like columns dotting throughout one layer. This is when the lava cooled from the inside upward, and the cooled sections of lava separated into these upward-pointing shafts.

“At

the bottom, you will see cross-bedded gravels and pillow layers,”

Horning said. “Near the top, you will see lavas with nearly vertical

cooling joints in the flows. They can interfinger or interlayer, depending

on water levels. Sometimes, lavas can squeeze in between deeper layers

to cool as sills, with vertical joint systems that look much like columnar

jointing of lava flows.”

“At

the bottom, you will see cross-bedded gravels and pillow layers,”

Horning said. “Near the top, you will see lavas with nearly vertical

cooling joints in the flows. They can interfinger or interlayer, depending

on water levels. Sometimes, lavas can squeeze in between deeper layers

to cool as sills, with vertical joint systems that look much like columnar

jointing of lava flows.”

Horning said everything is at a bit of an angle because the whole complex has been tipped to the west by about 15 degrees, so its eastern part has been lifted high into the sky.

|

|

Arch

Cape Property Services.

Dozens of homes in that dreamy,

rugged stretch between Cannon Beach and Manzanita known as Arch

Cape. Oceanfront and ocean view , or just a short walk from the

sea. |

|

STARFISH

POINT Newport - Offers only the finest in luxury condominium

lodging. Every unit is focused on the beauty of the sea and the

beach. |

Lincoln City Vacation Homes Something for everyone: smaller homes with a view to a large house that sleeps 15. All are either oceanfront or just a few steps away – all with a low bank access and fantastic views. Most are in the Nelscott area; one is close to the casino. You’ll find a variety of goodies: fireplaces, multiple bedrooms, dishwashers, Jacuzzis, washer/dryers, hot tubs, cable TV, VCR, barbecues; there’s a loft in one, and another sprawling home has two apartments. Pets allowed in some homes – ask first. Each comes with complete kitchens. Most have seventh night free. Prices range from winter $85 to summer $230 per night. www.getaway2thecoast.com. 541-994-8778. |

Inn

at Cannon Beach. Beautifully wooded natural setting at quiet south

end of Cannon Beach. Great during winter storms with a new book by

the fireplace – or when the sun is out for family fun and beach

strolling. Handsome beach cottage-style architecture. Lush flowering

gardens and naturalized courtyard pond. Warm, inviting guest rooms.

Continental buffet breakfast. Warm Cookies. Family and Pet Friendly.

Welcome gifts. Smoke-free. Complimentary Wireless Connectivity. Wine

and book signing events. 800-321-6304 or 503-436-9085. Hemlock At

Surfcrest, Cannon Beach, Oregon. www.atcannonbeach.com. Inn

at Cannon Beach. Beautifully wooded natural setting at quiet south

end of Cannon Beach. Great during winter storms with a new book by

the fireplace – or when the sun is out for family fun and beach

strolling. Handsome beach cottage-style architecture. Lush flowering

gardens and naturalized courtyard pond. Warm, inviting guest rooms.

Continental buffet breakfast. Warm Cookies. Family and Pet Friendly.

Welcome gifts. Smoke-free. Complimentary Wireless Connectivity. Wine

and book signing events. 800-321-6304 or 503-436-9085. Hemlock At

Surfcrest, Cannon Beach, Oregon. www.atcannonbeach.com. |

|

|

The Ocean Lodge. There will not be another property built like this in Cannon Beach in our lifetimes. Rare, premiere ocean front location; handsome, dramatic architecture and tasteful, fun (nostalgic) beach interiors. Overlooks Haystack Rock. 100 percent smoke free. Imaginative special occasion packages. Massive wood burning lobby fireplace. Library w/ fireplace, stocked with impressive book collection. Pet and family friendly. Lavish continental buffet breakfast. In-room fireplaces, mini-kitchens. Jacuzzi tubs in select rooms. DVD players, complimentary movies. Morning paper. Warm cookies. 888-777-4047. 503-436-2241. 2864 Pacific Street. Cannon Beach, Oregon. www.theoceanlodge.com |

RELATED STORIES

Click here for video of Dec. storm aftermath

Oregon Coast Best of Awards for the Year And the winners are: best of Oregon coast restaurants, lodgings, science, odd events in nature and stunning moments for 2007

Watching Transformations of Oregon Coast Beaches Seasons change and so do beaches, revealing different sides and a variety of eye-popping sights

Structures Found on Oregon Beach May Be 80,000 Years Old - They are the remnants of a forest apparently 80,000 years old, found at Hug Point

Day or Night Mysteries and Merriment on Oregon Coast It's more than just nightlife that comes to life, but the beaches offer major opportunities

Oregon Coast Travel Site Goes Wireless Provides Lodging Reports - Oregon Coast Beach Connection now has mobile lodging and dining listings, along with weekly lodging availability reports

SPECIAL

SECTIONS |

|||||||||||||

| oregon coast weather | |||||||||||||

| oregon coast mileage chart & map | |||||||||||||

| day trips, suggested itineraries | |||||||||||||

| Oregon Coast Lodging Specials | |||||||||||||

| Search BeachConnection.net's 1,000 pages | |||||||||||||

| Oregon Coast Real Estate | |||||||||||||

| Oregon Coast Pictures | |||||||||||||

| Atypical Things to Do | |||||||||||||

| Oregon Coast Camping | |||||||||||||

| Seaside, Oregon Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Cannon Beach, Oregon Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Manzanita, Wheeler, Rockaway Beach Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Lincoln City Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Depoe Bay Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Newport, Oregon Lodging | |||||||||||||

| Cannon Beach Complete Guide | |||||||||||||

| Lincoln City Complete Guide | |||||||||||||

| Seaside, Oregon Complete Guide | |||||||||||||

OR

TAKE THE VIRTUAL TOUR |

|||||||||||||

|

For weekly updated info on lodgings and accomodation reviews, see the Travel News section

CONTACT / ADVERTISE ON BEACH CONNECTION

Copyright Warning: All material on this page is owned by Oregon Coast Beach Connection/BeachConnection.net. Any redistribution - in any medium - of this article is stricly prohibited. You are welcome to provide a sample with a link to this page, however, or display our RSS feeds or our news headline feeds on your site.